The village where Satan lives, and emerges from time to time, is fenced with broken glass. There... planes crash iron-buildings down; cannibals taste German meat; Japanese teenagers kill themselves live on the internet; North-Americans shoot each other before school proms with supermarket guns; Palestinians blow themselves up on the wealthy streets of Tel Aviv; a Colombian goes mad and takes 30 diners to hell with him years after surfing in Vietnam for Uncle Sam; Theo van Gogh’s heart stabbed in Amsterdam by the hand of God. All the rest watch the show live on satellite TV.

Stop and rewind to the mad Colombian. He shot himself after a killing round that took place in an expensive Bogotá restaurant on the evening of December 4, 1986. A mature, lonely guy in his 50s, Campo Elías Delgado was studying Education at the Jesuit University in Bogotá, and survived teaching private English lessons. Before the restaurant spree, he killed other people in different spaces of the city. Among the day’s victims: his own mother and one of his English students, a 15 year old girl, a bloody Lolita, deflowered like an angel heart with a Vietnam war knife.

By 1986, Mario Mendoza, the prize-winning Colombian writer, was a senior student of Literature and Philosophy, also at the Jesuit University. He met Campo Elías Delgado early that year and during the second semester they shared a literary friendship, exchanging books and drinking coffee. On December 4, during his lethal journey, and already after the first killings, Campo Elías went to the university faculty and tried to find Mendoza, who was not around. They never met. But that final conversation, whatever it could have been, would stay in Mendoza’s imagination forever.

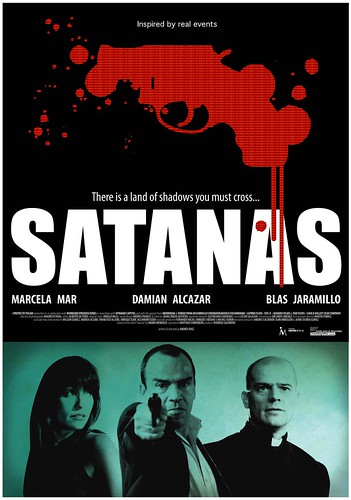

Fifteen years later, in 2001, Mendoza published his novel “Satanás” (Satan) about the events that preceded and surrounded the restaurant massacre. A hit in Colombia, the book won an important literary prize in Spain, took Mendoza to the next level in the cultural markets, and captured the attention of Colombian filmmakers Andres Baiz and Rodrigo Guerrero, who were at the final stages of their 8 years film training in New York, where they studied and gained experience working on different filmmaking tasks for heavy-weight projects.

When Mendoza’s novel caught their eyes they where working as production associates for the feature "Maria Full of Grace" (about hard drugs commerce between the US and Latin-America). Competition for the film rights of “Satanás” was already on, and the Baiz/Guerrero team would not be the only one bidding for the book. Months later, when negotiations finally arrived the filmmakers showed Mendoza and his publishing house a copy of “Maria Full of Grace”, to present their experience. The quality and progressive approach of “Maria” convinced Mendoza, and Baiz (the Director) and Guerrero (the Producer) got the rights. At the same time “Maria” would explode into one of the most important films of 2004-2005, getting top prizes at the Berlinale and later an Oscar nomination for best actress, skyrocketing the acting career of Catalina Sandino Moreno.

Enter 2007. Sympathy for the devil. Flash-forward through more than two years of getting the financing together, adapting the novel for the screen, shooting it in 6 weeks, editing for months, triggering the world film industry premiere at the 2007 Miami International Film Festival in March, a Best Picture award at the Monte Carlo Film Fest in May, and its public Colombian release on June 1st. Satanás, the film, is a dark tale about the urban world in early 21st century (or late 20th). An analysis of doomed lonely characters living doomed lives that cross at the wrong turns, lives whose common pinnacle will be a moment of hope, whose common abyss will be modern hell. A darker world than that other so superficially painful for the teenagers of Elephant. A simpler madness than the complex one that took a geometrical effort to map the Seven deadly sins. A similar world to that Travis Bickle’s New York of the mid 70s, with an insanity built up in ugliness, rejection and solitude, but without the happy ending of Taxi Driver.

Satanás follows the final steps of Campo Elías (Eliseo in the film) to a point in which the understanding of his circumstance makes him seem almost as innocent as the people he will kill… or as guilty. A solid film from firm filmmakers hands, slow paced, detailed, visually aware of the inner-multiplicity of the human soul, of its fragility, of its ultra-modern siege. The film was made with decision, knowledge of the craft, and not without thematic and financial risks. It constitutes a move forward for Colombian cinema within the new audiovisual industry context where globalization, state supported film initiatives, and a more flowing interaction with the Hollywood-industrial-cluster are the mixing elements. It also anticipates new exciting film careers and better, bigger, challenging movies originating in Colombia.

A strange thoughtful numbness might reach the audience by the end of the film, not horror, not relief, numb as they abandon the room and flow at night into the global-urban, wherever it is, not knowing who will be the next one to crack, at a northern university, at a mosque, during Christmas shopping, at a board of directors meeting, in the subway, after coming back from Baghdad or Rwanda, at the glance of the broken glass fence on the city’s edge... at the mercy of chance... expectant at the limbo... a blues for Satanás.

Carlos Peralta*

.

Watch the Trailer. Text in Spanish reads: "Do you believe in Love? Money? Forgiveness? Pain? Destiny? It does not matter what you believe in... you will face him: SATANas".

* The author of this short article is related to dynamo Capital, a Film Production and Financing company based in Colombia. dynamo was involved with the production of Satanás. However, when writing this review, the author tried to be as objective as possible... even though objectivity always proves to be so elusive, more so in the messed up world of today.

.